Test Overview

Stool Test analysis is a series of tests done on a stool (feces) sample to help diagnose certain conditions affecting the digestive tract. These conditions can include infection (such as from parasites, viruses, or bacteria), poor nutrient absorption, or cancer.

For a stool analysis, a stool sample is collected in a clean container and then sent to the laboratory. Laboratory analysis includes microscopic examination, chemical tests, and microbiologic tests. The stool will be checked for colour, consistency, amount, shape, and the presence of mucus. The stool may be examined for hidden (occult) blood, fat, meat fibers, bile, white blood cells , and sugars called reducing substances. The pH of the stool also may be measured. A stool culture is done to find out if bacteria may be causing an infection.

Stool tests in diagnosis and follow-up of gastrointestinal disorders in children:

Abstract

Stool is not just a simple waste material. Some stool tests can be easily used in primary care in the differential diagnosis of disorders such as gastrointestinal infections, malabsorption syndromes, and inflammatory bowel diseases. Stool tests can prevent unnecessary laboratory investigations. Stool analyses include microscopic examination, chemical, immunologic, and microbiologic tests. Stool samples can be examined for leukocytes, occult blood, fat, sugars (reducing substances), pH, pancreatic enzymes, alpha-1 antitrypsin, calprotectin, and infectious causes (bacteria, viruses, and parasites). Stool should also be macroscopically checked in terms of color, consistency, quantity, shape, odor, and mucus.

Keywords: Children, gastrointestinal disorders, stool tests

Introduction:

Important information about diseases that affect the gastrointestinal system can be obtained with stool examinations. Stool can be examined macroscopically, microscopically, chemically, immunologically, and microbiologically. Stool samples to be examined should be collected in a clean container, fresh or kept under appropriate conditions.

The aim of this review was to present the most up-to-date information about stool tests that have an important place in the diagnosis and follow-up of childhood gastrointestinal diseases.

Why It’s Done:

Stool analysis is done to:

- Help identify diseases of the digestive tract, liver, and pancreas. Certain enzymes (such as trypsin or elastase) may be evaluated in the stool to help see how well the pancreas is working.

- Help find the cause of symptoms affecting the digestive tract, such as prolonged diarrhea, bloody diarrhea, an increased amount of gas, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, bloating, belly pain and cramping, and fever.

- Screen for colon cancer by checking for hidden (occult) blood.

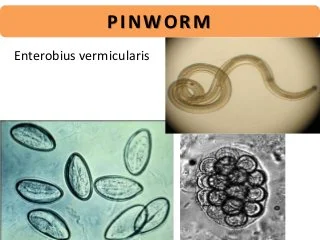

- Look for parasites, such as pinworms or Giardia.

- Look for the cause of an infection, such as bacteria, a fungus, or a virus.

- Check for poor absorption of nutrients by the digestive tract (malabsorption syndrome). For this test, all stool is collected over a 72-hour period and then checked for fat (and sometimes for meat fibres). This test is called a 72-hour stool collection or quantitative fecal fat test.

Preparation

Unlike most other lab tests, a stool sample is often collected by parents at home, not by health care professionals at a hospital or clinic.

If possible, your child may be asked to avoid certain foods and treatments for 2 weeks before the test, including:

- antacids, antidiarrheal drugs, and laxatives

- antibiotics and anti parasite drugs

- enemas

- contrast materials (liquids taken before some X-rays, CAT or CT scans, or other imaging studies)

Procedure

The doctor or hospital laboratory will usually provide written instructions on how to collect a stool sample. If instructions aren’t provided, here are tips for collecting a stool sample from your child:

- Be sure to wear latex gloves and wash your hands and your child’s hands afterward.

- Many kids with diarrhea, especially young kids, can’t always let a parent know in advance when a bowel movement is coming. So a hat-shaped plastic lid is used to collect the stool specimen. This catching device can be quickly placed over a toilet bowl, or under your child’s bottom, to collect the sample. Using a catching device can prevent contamination of the stool by water and dirt. Another way to collect a stool sample is to loosely place plastic wrap over the seat of the toilet. Then place the stool sample in a clean, sealable container before taking it to the lab.

- Plastic wrap can also be used to line the diaper of an infant or toddler who isn’t yet using the toilet. The wrap should be placed so that urine runs into the diaper, not the wrap.

- Your child shouldn’t urinate into the container and, if possible, should empty his or her bladder before a bowel movement so the stool sample isn’t diluted by urine.

- The stool should be collected into a clean, dry plastic jar with a screw-cap lid. For best results, the stool should be brought to the lab right away. If this isn’t possible, the stool should be stored in preservative provided by the lab and then taken there as soon as possible.

Macroscopic examination of the stool

Stool samples should be evaluated macroscopically in terms of color, consistency, quantity, form, odor, and presence of mucus. The presence of a small amount of mucus in stool is normal. However, the presence of copious mucus or bloody mucus is abnormal. The normal color is tawny due to the presence of bilirubin and bile. In infants, the stool may be green, its consistency may be watery or pasty. Stool color varies greatly depending on diet. Clay-colored or putty colored stool is observed in biliary obstructions. If more than 100 mL blood is lost from the upper gastrointestinal system, black, tarry stool is observed. Besides bleeding, black-colored stool may also be observed due to iron or bismuth treatment. Red-colored stool is observed in lower gastrointestinal tract bleeding.

Occult blood in the stool:

In peroxidase-based tests, peroxidase-like activity of hematin and/or hemoglobin transforms the catalyzer to blue. A restrictive diet may not be needed during the test. A systematic review demonstrated that sticking to a restrictive diet did not decrease the rate of occult blood positivity. Iron preparations ingested orally do not cause a positive hemoccult test. Ingestion of large amounts of vitamin C causes false-negative results and intake of vitamin C should be limited to less than 250 mg daily for at least three days before sampling. Before examination, stool samples should not be diluted again. Dilution increases the test’s sensitivity, but causes an increase in false-positive results. Aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may lead to false positivity by causing minor bleeding in the gastrointestinal mucosa. In addition, the test should be repeated with two samples daily for three days to increase the test’s accuracy. A loss of about 2–5 mL blood daily is normal in the intestines. Hemorrhages above this limit can be detected in the hemoccult test. Immunohistochemically occult blood tests were developed in order to measure human hemoglobin directly in the stool using monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies against the globin part of the human hemoglobin. It has high sensitivity and specificity in detecting lower gastrointestinal hemorrhages. In upper gastrointestinal hemorrhages, disintegration of the globin chain by proteases decreases the sensitivity. No special diet is required before the tests.

Detection of fat in the stool:

In healthy humans, daily excretion of fat in the stool is less than 6 g and this amount remains constant even if daily fat consumption is 100–125 g. Excretion of fat in the stool may moderately increase in the absence of fat malabsorption in patients with diarrhea. Values up to 14 g/day were reported in volunteers whose diarrheas were induced by laxatives and in patients whose stool weights were more than 1000 g/day. Therefore, a moderate increase in excretion of fat in the stool in a patient with diarrhea does not indicate that malabsorption is the primary cause and other investigations should be performed to determine the cause of the diarrhea.

Various tests may be used to detect fat malabsorption (steatorrhea). The gold standard in the diagnosis of steatorrhea is quantitative calculation of stool fat. For this objective, the stool is collected for 72 hours while the patient is on a diet containing 100 g fat daily. However, qualitative tests are also used as a screening tool for steatorrhea because it is considerably difficult to collect stool for 72 hours. The Sudan III stain and acid steatocrit tests are among these tests. These tests can be performed more easily and rapidly compared with the detection of fat in a 72-hour stool sample, but they could not be substituted for the 72-hour fecal fat test .

Fecal pH, electrolytes, and reducing substances:

After a fresh and watery fecal sample is homogenized and centrifuged, pH and electrolyte intensities are measured in the watery part of the feces. Fecal pH is measured in a fresh fecal sample using nitrating paper. Normally, the fecal pH ranges between 7.0 and 7.5. A fecal pH below 5.5 indicates acidic feces. In babies fed with breastmilk, the fecal pH is mildly acidic. The fecal osmolarity is equal to serum osmolarity (290 mosmol/kg). The osmotic gap is obtained by multiplying the sum of Na and K values in the fecal water by two and subtracting this value from the fecal osmolarity [osmotic gap= 290 – (Na + K) x 2]. Specifying the osmotic gap in the stool is important in patients with osmotic diarrhea. The osmotic gap is high in osmotic diarrhea (>125 mosmol/kg), and is small in secretory diarrhea (>125 mosmol/kg). This formula is preferred to direct measurement of fecal osmolarity because bacterial fermentation or contamination of fecal samples with concentrated urine after collection of the stool may lead to a falsely high osmolarity.

Entamoeba stool antigen test

Detection of entamoeba antigens in the stool is a sensitive, specific, rapid, and feasible method, and can differentiate E. histolytica and E. dispar. In the diagnosis of E. histolytica infection, commercial stool and serum antigen tests are available that use monoclonal antibodies to bind to the epitopes found on pathogenic E. histolytica strains. These epitopes are not found on non-pathogenic E. dispar strains. Kits that use ELISA, radioimmunoassay or immunofluorescence methods have been developed for antigen tests.

What to Expect

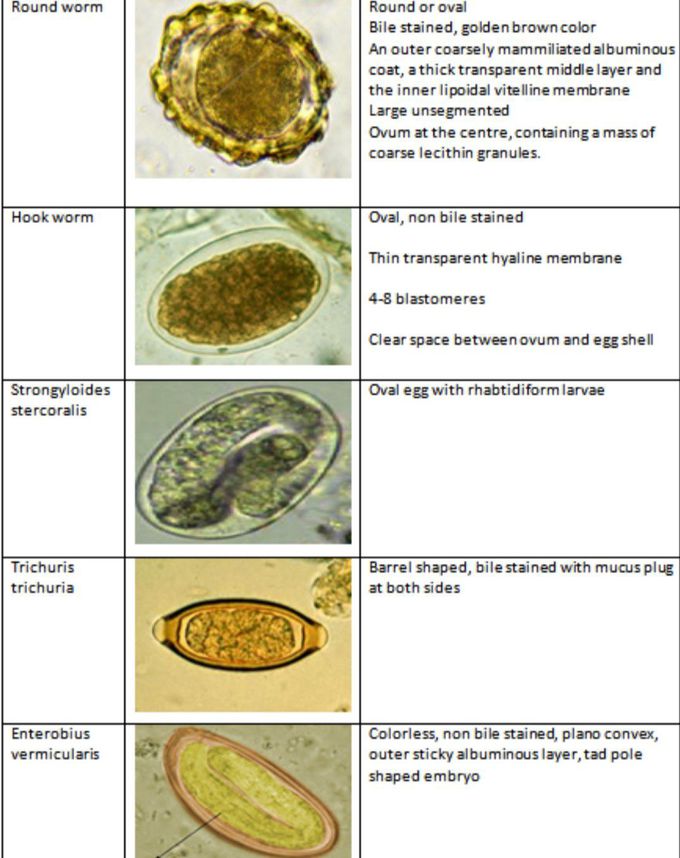

When the sample arrives at the laboratory, a technician stains some of the stool specimen with a special dye and views it under a microscope to identify parasites or ova that are present.

Getting the Results

In general, the result of the ova and parasites test are reported within 2 days.

Risks

No risks are associated with collecting stool samples.

Helping Your Child

Collecting a stool sample is painless. Tell your child that collecting the stool won’t hurt, but it has to be done carefully. A child who’s old enough might be able to collect the sample alone to avoid embarrassment. Tell your child how to do this properly.

If You Have Questions

If you have questions about the ova and parasites test, speak with your doctor.

[…] spreads through contact with food or water that has been contaminated by an infected person’s stool. Hepatitis A is an acute or short-term infection, which means people usually get better without […]

[…] discolored bodily discharge (dark urine or light stools) […]

[…] gray- or clay-colored stools […]

[…] This fever also called step ladder fever. The correct way to diagnose enteric fever is blood, or stool culture. If culture test is not available, a serology test its called widal test. Antibodies of salmonella […]

[…] Occult blood means that You Can’t see it with the naked eye. And fecal means that it is in your stool Blood in your stool means there is bleeding in the digestive tract Fecal occult blood is detected […]

[…] Lubricated and moist. It reduces the damage that may be caused by micro-organisms like fungi, viruses, and bacteria. Mucus can also provide by our stomach acid against there is very little mucus, in the stool. It is […]

Sounds okay written down, but-probably won’t work out in practice, sorry..

You made some clear points there. I looked on the internet for the topic and found most guys will approve with your website.

[…] Entamoeba histolytica, is a species of amoeba, a type of single-celled eukaryotic microorganism. It is the causative agent of amoebiasis, a gastrointestinal disease that can range from asymptomatic colonization to severe and potentially life-threatening infections. Here are some key points about Entamoeba histolytica: […]

[…] in this gene can lead to the production of abnormal or insufficient amounts of the alpha-1 antitrypsin […]

[…] investigations, An Ova and Parasite (O&P) test is a laboratory examination of a stool (feces) sample to detect the presence of […]